|

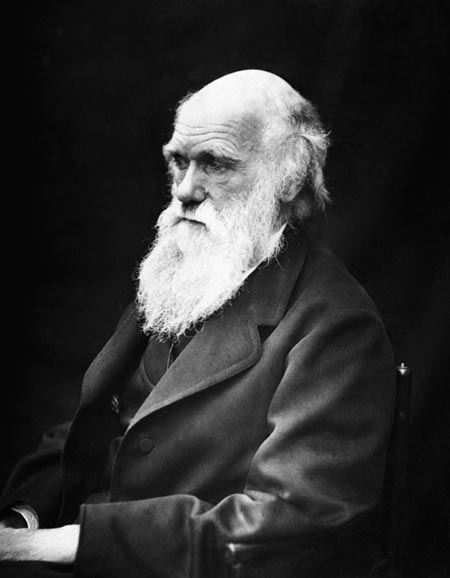

If ever there

was a contradiction in terms it must surely have been Christian Darwinism.

The name Christian might have been annexed to anti-Darwinism or perhaps

to some version of evolution which did honor to the purposes and character

of the Creator, but never, surely to that theory set forth by the agnostic

naturalist Charles Darwin. Yet Christian Darwinism did exist-the appellation

was used as early as 1867-and its representatives on both sides of the

Atlantic were among the ablest and most orthodox of the post-Darwinian

controversialists.

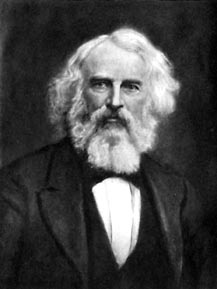

James

Iverach (1839-1922) was a professor of dogmatic theology and of

New Testament at the Free Church College in Aberdeen. The form in which

Iverach thought Darwin's theory might safely be held was not one of

agnostic evolution. The work of science is strengthened by the religious

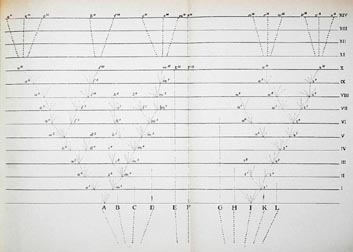

conviction that nothing occurs by chance. Darwin's theory of biological

evolution by natural selection could be seen from two points of view,

one strictly scientific and the other teleological. For the first, natural

selection offers only a fragmentary conception of nature. From the second,

the religious viewpoint, natural selection is seen as it truly is: as

an expression of the sum total of causes, internal and external, which

have transpired to the end that just those forms of life which are currently

observed should exist. Interpreted thus, natural selection does not

damage the argument from design but actually strengthens it.

Featured

work:

Theism

in the light of present science and philosophy / by James Iverach.

New York: Published for New York University by the Macmillan Co., 1899.

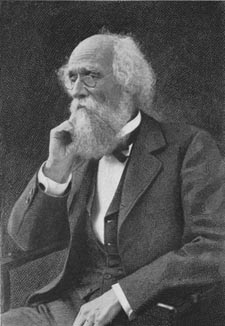

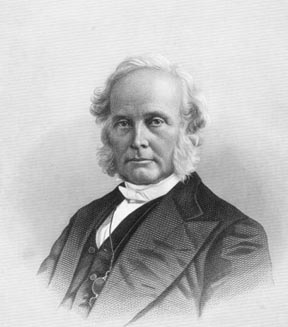

In the last

two decades of the nineteenth century Aubrey Lackington Moore (1843-1890)

was the clergyman who more than any other man was responsible for breaking

down the antagonisms toward evolution then widely felt in the English

Church. Unlike many theologians of his generation, Moore learnt to understand

the scientific enterprise as scientists themselves understood it. His

was a theology which refused to connect the Christian faith necessarily

with evolution or the denial of evolution, but which held that evolution

should be specially attractive to those whose first thought is to hold

and to guard every jot and tittle of the Catholic faith. Faith is not

dependent on any particular understanding of organic origins, for whatever

science may reveal as the method of origination, it is, after all, only

a revelation of God's method of creation. Evolution or creation is thus

a false antithesis. A Christian's controversy with a Darwinian agnostic

is a controversy with his agnosticism, not his Darwinism.

Featured

work:

Science

and the faith: essays on apologetic subjects / by Aubrey L. Moore.

3rd ed. London: K Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1892.

|